Gucci's Brand Strategy: UK vs China

- Nov 11, 2021

- 5 min read

Updated: Nov 7, 2022

Positioning

Gucci frequently altered its positioning in China, therefore, its effectiveness could be questioned because of the lack of durability by not having a consistent strategy. Tom Ford turned the house into, “a globally-understood synonym for S-E-X and celebrity”. Initially, the strategy was to gradually reposition away from this, eventually targeting multiple consumer segments. In 2012, however, Gucci adapted its strategy aiming to reposition itself in China to meet customer’s demand for sophisticated designs and begin a new era of class. Despite this, Gucci dropped below the top 5 for Chinese purchase intentions in 2019 for the first time. The brand, therefore, implemented nostalgia marketing, which is a successful yet contrasting approach, exemplified by Gucci x Mickey Mouse. In spite of the success, the positioning could be seen as distancing the brand from what makes Gucci Gucci. Its effectiveness could also be questioned because of the lack of distinctiveness. Lowe and Balenciaga had also implemented nostalgia marketing, which reduces Gucci’s ability to stand out.

Gucci altered its UK positioning aiming to reinforce the brand’s luxury and exclusivity and attract the corresponding consumers. This was no drastic strategy change like in China, potentially suggesting its UK positioning was more effective based off durability. It is important to highlight that in both countries Gucci appears to take a consumer-centric approach, positioning itself for the consumer. Kapferer and Bastien (2012) in their anti-marketing theory, however, argue that luxury brands should forget positioning and dominate the customer. This questions whether Gucci is a luxury brand, however, there are other factors used to define a luxury brand.

Communications

In China, as discussed above, Gucci uses nostalgia marketing which is implemented through its brand’s communications. The Chinese New Year campaign advert, for example, shows people experiencing Disneyland together. This implies that Gucci has adapted its communications to China’s highly collectivist culture because the advert shows people interacting in a group, therefore, better appealing to the Chinese consumer. Contrastingly, setting the advert in Disneyland could be criticised because it is designed for leisure and China is a restrained culture that has limited leisure time. This may imply that Gucci has not adapted its communications as effectively as it could, however, as highlighted above, the Gucci x Mickey Mouse collaboration was successful in China. Nonetheless, this may be because Chinese consumers positively respond to nostalgia marketing and the fact that the use of Disneyland is criticised, not Disney.

Contrastingly, for the UK, the Gucci Aria campaign utilises its sex strategy. The advert is “set in the secretive and seductive atmosphere of a hotel”. This suggests that Gucci has adapted its communications to the UK’s highly indulgent culture because the advert shows people freeing their desires, theorised by Hofstede Insights (2021). This implies that the advert is well-suited to British consumers, however, more communication types would have to be evaluated to establish the effectiveness of Gucci’s UK communication strategy. This advert could not be used in China because of its restrained culture. Furthermore, logomania designs are used in the advert meaning it also would not appeal to Chinese consumers due to the unsuccessfulness of these products in China.

Promise

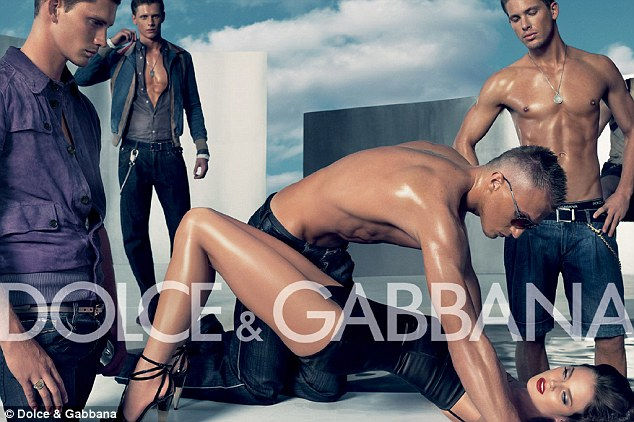

In China, Gucci promises to offer “the most desirable luxury products that combine authority in fashion with “Made in Italy” quality and craftsmanship”. It may be important to note that there is no mention of nostalgia here which suggests that it does not align to its repositioning and communication strategies. Whereas for the UK, it is to disrupt and innovate through an evolving vision. It could be argued that sex as a strategy is not innovative as other brands have done this, such as Dolce & Gabbana (D&G), as shown by Figure 3. However, it may also be argued that Gucci did disrupt when it implemented its gaming strategy, discussed further below.

Experience

Gucci globally utilises the four dimensions of brand experience scale, developed by Brakus et al. (2009). The brand executes the behavioural dimension of the scale most effectively through technology. Gucci was the first luxury fashion brand to go into gaming, creating its products for digital worlds such as, Zepteo, The Sims and Animal Crossing. Although this originally gave Gucci distinctiveness, other brands such as Hermès and Burberry followed, meaning Gucci no longer stands out against its competitors in this area. Nonetheless, this gave Gucci an initial competitive advantage. Gucci Arcade is a series of games on the app, which is mostly downloaded by the Chinese. Due to China’s retained culture, gamification can be criticised by Hofstede Insights (2021) because gaming is an indulgent activity. Nevertheless, gaming links with nostalgia marketing (shown to be successful in China) because these games may induce childhood memories.

Located in Florence, the Gucci Garden, as Figure 4 describes, could be argued that its sensory experience is not of the same level virtually as it is in real life which restricts this experience to Italy. Furthermore, in Milan, the Sensorium element of the Fast Company Innovation exemplifies an affective experience according to Brakus et al. (2009). Similar to the Gucci Garden, this experience is restricted to Italy and also cannot be viewed virtually. Currently, sensory and affective experiences have not been implemented outside Italy, therefore Gucci should execute all of the dimensions on the scale equally and globally to ensure a successful experience strategy.

Sources:

Chen, I., & Luk, S. (2017). Gucci: Facing Growing Challenges in China. Asian Case Research Journal, 21(2), 281-310.

Chitrakorn, K. (2021, January 24). Gucci, Loewe tap nostalgia marketing ahead of Chinese New Year. Retrieved November 2021, from Vogue Buisness: https://www.voguebusiness.com/companies/gucci-loewe-balenciaga-taps-nostalgia- marketing-for-asian-consumers

DeFanti, M., Bird, D., & Caldwell, H. (2013). Forever Now: Gucci’s Use of a Partially Borrowed Heritage to Establish a Global Luxury Brand. Varieties, Alternatives, and Deviations in Marketing History, 16, 14-23.

DeFanti, M., Bird, D., & Caldwell, H. (2014). Gucci’s use of a borrowed corporate heritage to establish a global luxury brand. Competition Forum, 12(2), 45.

di Marco, P. (2013, May 16). Brand Management on Gucci - Interview with CEO of Gucci. (S. Nagasawa, & T. Fukunaga, Interviewers)

Diderich, J. (2019, September 16). Gucci Losing Brand Heat in China. Women's Wear Daily, 4. Gucci 2.0. (2018, May 8). Gulf Business.

Gucci. (2021). About Gucci. Retrieved November 2021, from Gucci: https://www.gucci.com/int/en/st/about-gucci

Gucci. (2021). Gucci École de l’Amour. Retrieved November 2021, from Gucci Equilibrium: https://equilibrium.gucci.com/gucci-ecole-de-lamour/

Gucci. (2021). Gucci 100 Collection. Retrieved November 2021, from Gucci: https://www.gucci.com/uk/en_gb/st/capsule/gucci-100-collection

Gucci. (2021). Gucci Arcade. Retrieved November 2021, from Gucci:

https://www.gucci.com/hu/en_gb/st/gucci-games

Gucci. (2021). Gucci Garden. Retrieved November 2021, from Gucci:

https://virtualtourguccigarden.gucci.com/#/en/

Gucci. (2021). Gucci Garden Archetypes. Retrieved November 2021, from Gucci:

https://www.gucci.com/uk/en_gb/st/stories/inspirations-and-codes/article/gucci-

garden-archetypes

Gucci. (2021). Gucci Home. Retrieved October 2021, from Gucci UK: https://www.gucci.com/uk/en_gb/?gclsrc=aw.ds&gclid=CjwKCAjwzt6LBhBeEiwAbPGOg SpecXPRJe4Qem9Js9-

Gucci. (2021, 10 September). The Gucci Aria Advertising Campaign. Retrieved November 2021, from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ob570Cescv4

Gucci by Gucci: 85 years of Gucci. (2006). Thames & Hudson.

Gucci Equilibrium. (2021). About. Retrieved Novemeber 2021, from Gucci Equilibrium: https://equilibrium.gucci.com/about/

Gucci Equilibrum. (2021). Gucci École de l’Amour. Retrieved November 2021, from Gucci

Equilibrum: https://equilibrium.gucci.com/gucci-ecole-de-lamour/

Gucci: The Making Of. (2011). New York: Rizzoli.

Gucci's Made-to-Measure Service for Men. (2012). Instablogs.

Heinberg, M., Katsikeas, C., Ozkaya, E., & Taube, M. (2019). How nostalgic brand positioning shapes brand equity: differences between emerging and developed markets. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(5), 869-890.

Hofstede Insights. (2021). Country Comparison. Retrieved November 2021, from Hofstede Insights: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/china,the-uk/

McDowell, M. (2021, March 23). Inside Gucci’s Gaming Strategy. Retrieved November 2021, from Vogue Buisness: https://www.voguebusiness.com/technology/inside-guccis-

gaming-strategy

Nagasawa, S., & Fukunaga, T. (2014). Strategic Brand Management of the Luxury Brand GUCCI. Waseda Business & Economic Studies (50).

Satenstein, L. (2020, Febuary 7). Meet the Creator Behind the Ultimate Tom Ford-Era Gucci Fan Account. Retrieved November 2021, from Vogue: https://www.vogue.com/article/tom-ford-gucci-fan-account-justin-friedman-tomfordforgucci

Comments