Fashion Brands' Impact on Children and Adolescents

- Jess Portch

- Feb 4, 2022

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 7, 2022

What a person wears may be seen by everyone they come into contact with and have positive and negative impacts on the wearer. Children and adolescents may be more vulnerable to these implications.

Fashion brands have positive effects on children and adolescents when their products become a consumer’s possessions. Possessions are extensions of the self and are used as a form of self-expression that portrays how a person wants to be perceived and links to adolescents’ self-concept. This links to the idea of the postmodern consumer and fragmentation where people can be more than one person. This allows people to have freedom in their individuality, therefore, suggesting fashions brands allow children and adolescents to be seen in their own terms. It may, however, be argued that young children are dressed by their carers, taking away their self-expression. Social media allows people to further develop their extended selves, self-brand and “post self/selves into being”. 55% of 5-15-year olds used social media in 2020 and this increased with age, implying that these consumers have a significant presence on social media thus strengthening their self-expression. This links to ideal self-congruence where fashion brands relate to consumers from their ideal perspective which is said to be used when consumers want to increase their self-esteem. This is, however, not necessarily who the person actually is which may be argued as deceiving and superficial. Younger consumers, in particular, also place a stronger emphasis on possessions and their sense of self could diminish if these possessions are lost. This raises the question as to whether this should be the core of how people are seen. Despite this, possessions provide the needed support for the self suggesting that fashion brands, supported by their products as possessions are important in improving children and adolescents’ sense of self and therefore their lives.

Fashion-related possessions also seem to provide social acceptance for children and adolescents. People have a need to belong and be accepted within a social group. For young consumers, fashion reinforces this as it allows them to fit in with peers. Clothes are symbols that help people to understand others and when considering friendships, provide an indicator of someone’s personality. This, therefore implies that fashion brands help children and adolescents to signal and receive messages that are important in forming relationships. It is, however, argued that children are less likely to understand clothing symbolism, which might mean that they are misunderstood by others and vice versa. Additionally, the constant seeking of approval from peers, creates pressure to make correct consumption choices and peer rejection decreases self-esteem. Fashion brands potentially reinforce this by crafting their perception of wealth in a materialistic way, evoking social comparisons which may lead to exclusion and isolation unattained. This potentially encourages materialism and superficiality in children and adolescents who do not question brands, leaving them vulnerable to brand communications. In contrast, it could be questioned whether the pressure of social acceptance is the fault of fashion brands or if it actually comes from society. This suggests that fashion brands may be important for children and adolescents because they provide the needed sense of belonging.

On the other hand, fashion brands have negative effects on children and adolescents as they may not be accessible for everyone. For instance, a low-income restricts consumption and this inability to follow trends may damage self-concept, especially in adolescents, resulting in increased vulnerability to interpersonal influences thus increasing the “negative socio-psychological impacts of living in poverty” and creating a “vicious-cycle”. This lack of possessions causes judgement from others and creates negative feelings towards self-image. Furthermore, social media may increase the opportunity for negative judgements because users are being validated by others on the brands they display, potentially leading to decreased self-esteem. This is particularly impactful for low-income adolescents as they struggle to resist brands. This shows that the inability to wear branded clothing negatively effects young consumers’ well-being, theoretically more than older consumers. Despite this, low-income consumers are more interested in low-status brands, such as Walmart, which tend to be more affordable. This may suggest that these consumers do not worry about wearing high-status brands. It could further be argued that members of their social groups also do not wear these brands meaning that not wearing them, makes them more accepted in the group. Nonetheless, unbranded possessions make a child unfavourable and unpopular to other children, leading to teasing. This, therefore, suggests that fashion brands worsen low-income children and adolescents’ lives. However, this is not representative of all income groups as it is specific to low-income consumers.

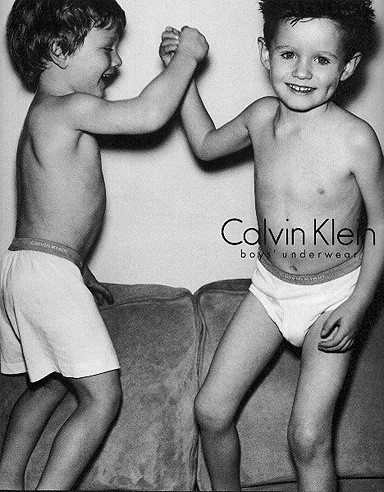

In contrary, fashion brands appear to be found to negatively affect children and adolescents from all income groups as they are increasingly targeting these consumers using unethical tactics. Fashion brands are said to sexualise children in advertisements, such as Calvin Klein’s 1999 campaign, showing young boys in underwear. Fashion brands are also said to sexualise children’s clothing, such as Asda’s George selling lacey lingerie for 9-year olds. This adultification of girls’ clothing leads to body image issues where they feel pressured to have sexy bodies. Furthermore, this loses children the right to be children, encourages paedophilia and sexual abuse. It is, however, argued that it is not down to brands to limit choice, it is down to consumers and ultimately, if there is no demand then brands would not produce the products. Furthermore, argue that Western society considers the display of particular body parts as a signal of the wearer’s sexual desire. This infers that fashion brands would not be unethical if consumers were not purchasing from them, therefore, society could be to blame for sexualising children. Despite demand, it is proposed brands have a moral obligation to not harm people. This, therefore, suggests that fashion brands produce products and advertisements that may harm children and adolescents’ well-being, which may result in trauma and extend into adulthood.

In conclusion, fashion brands facilitate self-expression by allowing children and adolescents the freedom of individuality where they can be seen in their own terms. In some cases, however, children’s clothes may be chosen by adults. Despite this, fashion brands fulfil the need to belong within a social group by helping children and adolescents to form relationships with others based on the wearing of their products. Nevertheless, these consumers potentially have limited understanding of clothing symbolism meaning they may signal and receive the wrong messages. Branded fashion products are also not accessible to everyone, such as low-income children and adolescents, potentially leaving them to become an outcast and subject to negative judgement and teasing, which damages their self-esteem. Furthermore, fashion brands’ products and advertisements can sexualise children and adolescents which encourages paedophilia and sexual abuse. It may, however, be questioned whether this is the fault of fashion brands in producing the products and advertisements, or if it is society’s fault for perceiving it this way.

Sources:

Alwi, S., Ali, S. M., & Nguyen, B. (2017). The Importance of Ethics in Branding: Mediating Effects of Ethical Branding on Company Reputation and Brand Loyalty. Business Ethics Quarterly, 27(3), 393-422. https://doi.org/10.1017/beq.2017.20

Astakhova, M., Swimberghe, K. R., & Wooldridge, B. R. (2017). Actual and Ideal-self Congruence and Dual Brand Passion. The Journal of Consumer Marketing, 34(7), 664-672. http://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-10-2016-1985

Belk, R. (1988). Possessions and the Extended Self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(2), 139- 168.

Buckingham, D. (2011). The Material Child: Growing up in Consumer Culture. Polity.

Firat, A. F., & Shultz, C. J. (1997). From Segmentation to Fragmentation: Markets and Marketing Strategy in the Postmodern Era. European Journal of Marketing, 31(3), 183-207. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000004321

Hamilton, K. (2012). Low-income Families and Coping through Brands: Inclusion or Stigma? Sociology, 46(1), 74-90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038511416146

Hunt, S. D. (2019). The Ethics of Branding, Customer-Brand Relationships, Brand-Equity Strategy, and Branding as a Societal Institution. Journal of Business Research, 95, 408- 416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.044

Isaksen, K. J., & Roper, S. (2008). The impact of branding on low-income adolescents: A vicious cycle? Psychology & Marketing, 25(11), 1063-1087. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20254

Isaksen, K. J., & Roper, S. (2012). The Commodification of Self-Esteem: Branding and British Teenagers. Psychology & Marketing, 29(3), 117-135. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20509

Jian, Y., Zhou, Z., & Zhou, N. (2019). Brand Cultural Symbolism, Brand Authenticity, and Consumer Well-being: The Moderating Role of Cultural Involvement. The Journal of Product and Brand Management, 28(4), 529-539. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-08- 2018-1981

Jiang, J., Zhang, Y., Ke, Y., Hawk, S., & Qiu, H. (2015). Can’t buy me friendship? Peer rejection and adolescent materialism: Implicit self-esteem as a mediator. Journal of experimental social psychology, 58, 48-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2015.01.001

Kim, H., & Sherman, D. (2007). "Express Yourself": Culture and the Effect of Self-Expression on Choice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.1

Limkangvanmongkol, V. (2015). Brands at the Point of No Return: Understanding #DRESSFORYOURSELFIE Culture as Post-postmodern Branding Paradigm. ACR Asia- Pacific Advances, 11, 51-56.

Ofcom. (2021). Children and Parents: Media Use and Attitudes Report 2020/21. Making Sense of Social Media.

Piacentini, M. (2010). Children and Fashion. In D. Marshall, Understanding Children as Consumers (pp. 202-217). SAGE Publications.

Piacentini, M., & Mailer, G. (2006). Symbolic Consumption in Teenager's Clothing Choices. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 3(3), 251-262. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.138

Pilcher, J. (2011). No logo? Children’s Consumption of Fashion. Childhood, 18(1), 128-141. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568210373668

Strasburger, V., & Wilson, B. (2002). Children, Adolescents and the Media. Sage Publications.

Tuan, Y.-F. (1980). The Significance of the Artifact. Geographical Review, 70(4), 462–472.

Vänskä, A., & Malkki, E. (2019). Fashionable Childhood: Children in Advertising. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474286008

Walasek, L., Bhatia, S., & Brown, G. (2018). Positional Goods and the Social Rank Hypothesis: Income Inequality Affects Online Chatter about High- and Low-Status Brands on Twitter. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 28(1), 138-148. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcpy.1012

Comments